L.A. Son Read online

DEDICATION/EPIGRAPH

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO MY AMAZING WIFE

AND DAUGHTER, JEAN AND KAELYN, WHO I DON’T WRITE

ABOUT MUCH IN THIS BOOK BECAUSE THE MOMENTS

WE SHARE TOGETHER ARE OUR OWN. I LOVE YOU GUYS

FOREVER AND EVER AND EVER AND EVER.

“FOR IT IS EASY TO CRITICIZE AND BREAK DOWN THE SPIRIT

OF OTHERS, BUT TO KNOW YOURSELF TAKES A LIFETIME.”

“THE POSSESSION OF ANYTHING BEGINS IN THE MIND.”

—BRUCE LEE

CONTENTS

DEDICATION/EPIGRAPH

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. MOTHER SAUCES

KIMCHI

ABALONE PORRIDGE

TWICE-COOKED DUCK FAT FRIES

CHILI SPAGHETTI

2. SILVER GARDEN

DUMPLING TIME

KOREAN CARPACCIO (SORT OF)

INSTANT PICKLED CUCUMBERS

POTATO PANCAKES

KIMCHI STEW

3. NECK FROZE

LEBANESE BEE’S KNEES

CHORIZO FOR BREAKFAST, CHORIZO FOR LUNCH, CHORIZO FOR DINNER, CHORIZO TO MUNCH

WINDOWPANE SMOOTHIES

CHINATOWN ALMOND COOKIES

PIE, GIVE THEM PIE! PECAN PIE WILL DO.

4. NOLAN RYAN

MAGIC FISH DIP

FRUIT ROLL UPS AND DOWNS

CHIPS AND DIP

THAT’S SO SWEET

5. GROVE STREET

CARNE ASADA

BEEF JERKY

YELLOW RICE AND GOAT STEW

PORK AND BEANS

KUNG PAO CHICKEN, PAPI STYLE

SALSA VERDE

HORCHATA

SPLASH

6. CRACK

PERFECT INSTANT RAMEN

GHETTO PILLSBURY FRIED DOUGHNUTS

KETCHUP FRIED RICE

CHEESE PIZZA, DOUGH TO SAUCE

BUTTERMILK PANCAKES

7. YOU VERY LUCKY, MAN

PORK FRIED RICE

MY MILK SHAKE

KALBI PLATE

SPAGHETTI JUNCTION: THE $4 SPAGHETTI THAT TASTES ALMOST AS GOOD AS THE $24 SPAGHETTI

CASINO PRIME RIB

PHO FOR DEM HOS

8. EMERIL

KOREAN-STYLE BRAISED SHORT RIB STEW

SOYBEAN PASTE STEW

SPICY OCTOPUS

KOREAN STAINED-GLASS FRIED CHICKEN

YUZU GLAZED SHRIMP OVER EGG FRIED RICE

HIBACHI STEAK TEPPANYAKI

GUMBO

9. NEW YORK, NEW YORK

POTATOES ANNA BANANA

SEARED BEEF MEDALLIONS WITH SAUCE ROBERT

VEAL STOCK

COCONUT CLAM CHOWDER

POUNDED PORK SCHNITZEL

SEARED SCALLOPS WITH CHIVE BEURRE BLANC

10. THE PROFESSIONAL

BIRRIA

CRISPY DUCK BREAST WITH POLENTA AND SWEET AND SOUR MANGO SAUCE

RED ONION MARMALADE

SIMPLE CLUB SANDWICH

EASY DE ANZA COBB SALAD

SIMPLE CHICKEN PICCATA

FRIED RIBS. WHAT?!

FRENCH ONION SOUP

CAESAR SALAD

MUSHROOM QUESADILLA

BROILED HALIBUT WITH SOY GLAZE

11. FISH SAUCE

EGGPLANT CURRY OVER RICE

CHICKEN SATAY WITH PEANUT SAUCE

COCONUT RICE

CARDAMOM MILK SHAVED ICE

SPAM BÁNH ME

HAINAN CHICKEN, KIND OF

CRÈME BRÛLÉE

12. WINDSHIELD

BEEF CHEEK TACOS

ROY’S BURGER

L.A. CORNER ON THE COB

KIMCHI AND PORK BELLY STUFFED PUPUSAS

L.A. DIRTY DOG

SESAME-SOY SALAD DRESSING

13. VEGETABLES 1-2-3

ASPARAGUS

BABY BOK CHOY

BROCCOLI RABE

BRUSSELS SPROUTS AND KIMCHI

ROASTED CAULIFLOWER

ROASTED MUSHROOMS

QUICK SPINACH SOUP

ROASTED SWEET POTATOES

SLOW-ROASTED TOMATOES

ZUCCHINI FRITTER OMELET

WATERMELON AND GOAT CHEESE

BUTTER PINEAPPLE

SALTED MANGO AND CUKES

THE RULES

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THANK YOU TO ALL OF YOU IN AND OUT OF OUR LIVES.

GRACIAS POR TODO.

THIS BOOK IS A PART OF YOU, TOO.

—ROY, TIEN, AND NATASHA

INTRODUCTION

HELLO. I’M ROY. Get in. We’re going for a ride.

Right around the time I started writing this story, I picked up a book about tribal tattoos, written by a Samoan chief. The opening line began, “I had to write this book.” That first line was so powerful to me. It struck me then, as I started putting the pages of my life together, and it strikes me now, as I sit here writing this introduction after, funnily enough, having finished this book. He wrote that line because he was compelled to tell the story of his tribe and his islands. Because he thought it was his destiny to help keep former generations alive by documenting the folklore, the information, and the stories that are passed down through the art of the tattoo. So it wasn’t that he wanted to write that book. He had to. It was his spiritual duty.

In a small, weird way, I feel the same about this book.

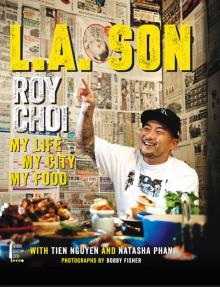

I had to write this book. To tell the story of my journey from immigrant to latchkey kid to lowrider to misfit to gambler to a chef answering his calling. To tell a story of Los Angeles and the people who live here. And to preserve it all on wax.

But before we get knee-deep in the messy yet beautiful chapters of my life, maybe it’ll help to have a little map in your pocket. L.A. is a huge place, and sometimes the glare of stereotypes and television screens blinds visitors to its true character, the amazing cultural diversity of our residents and the food. That muthafuckin’ L.A. food.

So let me play tour guide for a minute and show you around.

We’ll start in the same place I started when I immigrated here with my family from South Korea in 1972: Olympic Boulevard and Vermont Avenue. This is a big intersection in the middle of a neighborhood that’s now the hardworking community of Koreatown, where the smoke from the Korean BBQ grills will stick to your hair for days no matter which fancy shampoo you choose and where you’ll wash down your beers with crispy Korean fried chicken before hitting a multitude of other bars. A few miles north of here is Hollywood, and a dozen miles to our west is Sawtelle Boulevard, a little street with some of the best ramen and sushi in the country. Keep going west to see the canals of Venice and to kiss the sands of Malibu. UCLA and Beverly Hills aren’t too far from the beaches, and if we hop northbound on the 405 and 101, we’ll hit the San Fernando Valley—Granada Hills, Burbank, Tarzana, Sherman Oaks. Or if we ride the 405 southward instead, we’ll drive right into the cradle of the South Bay—Torrance, Gardena, Carson, Long Beach.

East of Koreatown is Downtown proper, where Hill and Broadway split like wooden chopsticks through Chinatown and the wind tunnels of Pershing Square whoosh us through the Jewelry District. Farther northeast of Downtown is a whole other world: the hills of Pasadena, the tacos and burritos and families in East L.A. and Boyle Heights, the amazing noodles and ph and soup dumplings in the San Gabriel Valley.

And there’s so much more: from the SGV, we’ll jump down the 710 or 605 freeway and drive through Commerce or Bell Gardens, passing factories and a casino or two along the way. Roll down your window and smell the sweet drippings of lechón and carne asada smoking in backyards as we swing by Cerritos or Whittier. Keep going south, and there they

are, our neighbors, Orange County and Riverside.

To loop back to L.A., we’ll head up the 110 freeway, pull off in South Central and Inglewood for a hot minute to ride the wide streets and grub on BBQ and soul food, and then swoop west on the 10 freeway, through Downtown, to end up right back where we started—right here on the corner of Olympic and Vermont, the heart of Koreatown.

I know. We covered a lot of ground. But don’t sweat it. I got the wheel and a full tank of gas. All you have to do is sit back and trust. In the pages that follow, you’ll see a little bit of this magical city through the lens of my life and through the food of the people who really live here. Through all of that, you’ll start to understand this amazing place that I was raised in and taste the flavors of the streets of L.A.

Thank you for picking up this book. Thank you for joining me on this ride through the crooked journeys of my life. L.A. welcomes you, and I welcome you, with love.

Oh, by the way, are you hungry?

Let me cook for you.

I got that, too.

You’re riding shotgun with Papi now. What could possibly go wrong?

NOTE:

BEFORE DIVING INTO THE RECIPES, FLIP TO ESSENTIALS AND CHECK OUT INGREDIENTS YOU MIGHT NEED TO STOCK UP YOUR PANTRY.

CHAPTER 1

MOTHER SAUCES

Seoul, South Korea, 1970. A hospital room in the heart of downtown Chongro-gu. A baby with a big Frankenstein head, drenched in his own blood, with more spewing out through his upper cleft like lava erupting from a volcano. Wailing, crying. Yeah, they stitched me up all right, but when the rumble in the jungle was over, I had a fat lip and a Harry Potter scar between my mouth and nose. One hell of a hectic entry into this world, huh?

MY PARENTS ACTUALLY MET IN Los Angeles in 1967. They were in Korea before then, on opposite sides of the country in fact. My mom’s from the most famous province in the North, Pyung-An Do. It’s cold up there, where the country meets China. I don’t know too much more, as Communism has washed away a lot of history, and it’s taboo to talk too much about it in the South, but I do know that the herbs and plants there would make even Humboldt County blush. And I know that my mom’s family took those raw ingredients and turned them into something pretty spectacular. As family legend had it, they had a magic touch: Sohn-maash. Flavors in their fingertips. Flavors that had been passed down over thousands of years, from generation to generation to generation, flavors that were now part of their very spirit. My mom grew up on things like mandoo, dumplings filled with mountain herbs mixed with ground meat and seafood. And naeng myun, cold buckwheat or arrowroot noodles, done two ways, both cold. One’s served in ice-cold beef broth with mustard and vinegar. The other has dried skate mixed in with the deadliest of the deadly chile pastes and filled with garlic, leaving your dragon’s breath stinking for days. Fucking delicious.

My mom was sister number four and child number five, right after my first uncle. She actually was supposed to be a boy but came out a girl, so they flipped around a Korean boy’s name. Nam Ja is man in Korean; make it Ja Nam and you got my mom. She went to the second-best all-girls school in the country, Jin Myung, and even though her grades weren’t the best, she was the queen bee of her crew, and she ruled the school. She continued on to Hangyang University. Then, in 1966, when she was all of twenty years old, my mom decided to take herself to the next level and head to America. The story was, she was going to the United States to attend “art school.” If you saw a photo of her at the Gimpo Airport, though, ready to cross the great Pacific, you’d see her outfit showing more art than school: Jackie O. gear, big stunner shades, a beautiful handbag. She was young, sassy, and pretty. How could the City of Angels be all that tough?

MY DAD, MEANWHILE, is from Chollanam-do in the South. That’s a province known for its food and the temper of its people: all that spicy, pungent, funky stuff you may associate with Korean food—from kimchi to pickled intestines and even to bi bim bap—comes from this province. Now don’t get me wrong—the rest of Korea has kimchi, too. It’s just this southwest region has the stinkiest, and it’s the most brash. And, like flamingos pink from plankton, the people are what they eat: tough, rude at times, abrasive, dominant, vivacious, conniving. Everybody hates the Cholla people, sometimes in envy and sometimes for good reason. But the freakin’ food no one can deny.

That’s where my dad’s from. It’s proper, then, that he was a badass muthafucka.

Even at ten, my dad was smart and tough as nails. He had to be. His mom had died by then, and so it was just him, his dad, his stepmom, and his older sister. And when the North invaded the South in 1950, the whole family had to flee the stampede of North Korean armies pushing southward. Eating scraps and old, cold rice, they fled from Seoul, going farther and farther south through Busan and Gwangju, settling down and then taking off again when the fire got too close. For my dad, that meant enrolling in a new school every time they moved, and that meant he was always the new kid, picked on and bullied by the local kids. But, really, all that just toughed him up more. As the family bounced from town to town, he bounced the local competition: with the same strategy that rules any street in the world, he would find the toughest dude on campus and challenge him to a shil-lim-style wrestling match. Shil-lim’s like sumo, but without the weight and with a sudden-death point system: first on his back loses. My dad never was first on his back.

Then he went gangsta in the classroom, Pac-Man eating up the competition. Kyunggi High School, the Phillips Exeter of Korea. Check.

Seoul National University, the Harvard of Korea. Check.

First commander as liaison with the U.S. Army. Check.

He got so high up the chain of command that in 1963 he was sent abroad to an Ivy League school to study diplomacy, international politics, and the Western way of life. With no money and no firm grasp on the English language except for a slippery handle on what he got from memorizing the fucking dictionary, he got through the University of Pennsylvania’s master’s program. Just so he could be that perfect foreign policy diplomat of the future. And as if that weren’t enough, he ran the mail room at ABC for Dick Clark. Mr. Incredible.

He wasn’t done yet. Like other Korean students sent to the United States to study, he was heading to another university to finish his education and get some more perspective on this new Western life of his, so he could take home what he knew and become a leader. He started his Ph.D. program at the University of Colorado at Boulder, then transferred to the land where the weed is green and the sunshine sets on the hydraulics, slow and low. This was Los Angeles, UCLA, Lew Alcindor. 1965.

In the land of sun, he had jobs in shadows: washing dishes at Lawry’s, janitorial duties throughout the city and on the north shore of Lake Tahoe during ski season. It was rough work, but he did what he had to do to survive. I think this was when he also started to party a little more, and he, the perfect Clark Kent, slowly transformed into a real man. A real man who wasn’t perfect, who was okay with having a little dirt under those properly trimmed nails.

That’s when he met a party girl. My mom. He pulled down his Wayfarers, lit a cigarette, and ripped straight game on her. They moved in together in an apartment off Crenshaw Boulevard and got married in a church on Jefferson and Vermont near the University of Southern California. He in a white tux, she in a simple, beautiful white gown with a veil centered with flowers. He never finished his Ph.D.

The late 1960s was a cool-ass time in Los Angeles. The Beach Boys, total Mod skinny tie shit, big long Chevys in cobalt blue cruising under bright green palm trees and the amber glaze of the California sunshine. They soaked in the L.A. sun and honeymooned in Europe. They returned to L.A., but this time it wouldn’t stick. Just one year after walking down the aisle, they bid UCLA good-bye—art school? what art school?—and off they went back to the country they had worked so hard to leave. In 1969, this meant returning to a country ruled by a dictator, Park Chung-hee, and an economy marked not by the flat-screens, semiconductors, and other bomb-a

ss toys of today but by heavy, raw industry. They took a step to the First World, then took two steps back to the Third. That’s Korean guilt and Confucian good son shit in play right there.

ONE YEAR AFTER COMING HOME to Korea, they welcomed me into their world. Stitched up as I was, you’d think I would have been treated differently, but in Korea it doesn’t matter if your mouth has one hole or two. You don’t baby the baby, and there was no such thing as “baby food.” So as soon as I got off my mom’s milk, they had a whole kitchen going for their little boy. No teeth? Man up, boy! You gotta be strong and healthy. The food has to build your brain!

So we’d get our Elton John on with electric griddles and butane burners surrounding my mom and aunts like pianos and keyboards. They’d feed us straight from the pan, straight off the griddle, always straight out of their fingers: try this, taste this, eat that. Chap chae, vermicelli noodles layered with julienned vegetables, egg, and marinated beef as complex and fly high as a J Dilla track. Daikon soup, abalone porridge, blended mung bean, soybean, and tofu soup mixed with rice, spinach, anchovy broth, and noodles. I slurped raw kimchi from stained Rubbermaid gloves. I was hand-fed bits of savory pancakes filled with pureed mung beans and scallions, sometimes studded with oysters. Flavor after flavor. Sohn-maash.

Life was tough, though. Money wasn’t flowing. My mom had married the “perfect” man, but the gravy train was starting to derail. My dad initially left Korea ahead of his class, but he came back behind the times. The classmates he had once eclipsed now shone in powerful positions in the government and universities. He was forced to kiss the ass of the people he had run circles around just a few years earlier. And still nothing. Then there was the indignity of it all: even if he was given a decent position, how could he work for the guy he used to boss around?

And then me. In a land of conformity, what of the boy with the deformity?

I don’t know how it exactly went down, but after almost two years back in Seoul, with no money, no job, and that lingering cognac lipstick film on their lips from the amber sunshine and cool palms of Los Angeles, they must have started to prepare. And in 1972, they finally packed it all up, snuck on a plane, and said, “Peace out, muthafuckas.” I would have, too.

L.A. Son

L.A. Son