L.A. Son Read online

Page 3

Dump the Idaho potatoes into the fat, in batches if necessary to avoid crowding, and, moving them constantly, cook until they’re slightly colored, about 3 minutes. Transfer them to the paper-towel-lined sheet pan. Repeat for the sweet potatoes and yuca; look for a light, light beige color, letting the fat come back to 250°F between batches.

Once all the tubers have been par-blanched, bring the fat up to 350°F and fry each batch again until crispy, 4 to 5 minutes, or a deep golden brown color. Scoop each batch onto the paper-towel-lined sheet pan. Sprinkle with sea salt and squeeze limes all over.

Fry the Thai basil leaves in the fat until crispy, about 2 minutes, and toss with the fries.

EAT NOW.

CHILI SPAGHETTI

* * *

Chili spaghetti at Bob’s Big Boy, milk shakes, root beer floats, late-night movies, repeat—that was our family fun. My parents took me to some raw-ass movies: Midnight Express, Taxi Driver, The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, Jaws, The Deer Hunter, The Exorcist, Dog Day Afternoon. Man, I was only five years old, homie! I don’t know what they were thinking, but those movies were great! I felt so alive being up so late, watching crazy movies, and eating spaghetti topped with chili. I wasn’t in bed by eight—ya know what I mean?

SERVES 4 TO 6

¼ cup plus 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

2½ pounds ground beef

1 large onion, minced

5 garlic cloves, minced

12 ounces tomato paste

1 tablespoon cider vinegar

2½ cups beef stock, homemade if you’ve got it, canned if not

One 4-ounce can diced green chiles

1½ jalapeño peppers, minced

1 tablespoon ancho chile powder

1 tablespoon cayenne

3½ tablespoons ground cumin

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon dried oregano

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon canned crushed pineapple

3 tablespoons chopped fresh cilantro

Kosher salt

1 pound spaghetti

GARNISH

¾ cup grated cheddar cheese

½ cup minced onion

Bottle of Tabasco sauce for the table

Heat the vegetable oil in a large saucepan over medium heat for about a minute. Add the beef to the pan and brown it. Transfer the beef from a pan to a bowl, leaving the oil in the pan.

Raise the heat to medium-high and add the onions and garlic to the pan. Cook until soft and lightly browned, 3 to 5 minutes.

Add the tomato paste to the pan, stirring and cooking the paste just slightly for about 2 minutes. Add the vinegar to deglaze the pan, then add the stock and the ground beef. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat to a simmer. Simmer for 30 minutes, then add the green chiles with their liquid, the jalapeños, chile powder, cayenne, cumin, oregano, pineapple, and cilantro. Simmer for 30 more minutes.

Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil and add the spaghetti, cooking until al dente, 8 to 10 minutes.

Drain the spaghetti and transfer to a big bowl. Pour the chili over the spaghetti and garnish with the grated cheddar cheese and minced onions.

TAKE IT OUT TO THE TABLE

TO SERVE FAMILY STYLE,

OPEN THE BOTTLE OF

TABASCO, AND SPLASH.

CHAPTER 2

SILVER GARDEN

WELCOME TO

SILVER GARDEN

Open 11am – 9pm

We accept Visa, Master Card, American Express, Diner’s Club

Please seat yourself

***

Silver Garden was a family restaurant. My family’s restaurant. Deep in Orange County, there was no other Korean restaurant around at the time that had food quite like we did. It was in the right place at the right time, until it wasn’t.

MY PARENTS DIDN’T CHOOSE the restaurant business so much as it chose them. Sales for their hippie jewelry faded as the seventies switched gears from Peter, Paul and Mary to the Bee Gees, and they had to look somewhere else for work. By then, everyone in the L.A. Korean community knew about my mom and her legendary food and homemade kimchi. Her kimchi was so good that not only family and friends, but also friends of friends and friends of friends of friends, straight up bought it off her. She took orders, cooked up a red storm at home, then packed it all up in Styrofoam containers. I’d pack those into cardboard boxes, and off we’d go to make home deliveries. Everything spilled in the car, my parents fought, but my mom made it happen.

PANCHAN ARE LITTLE SIDE DISHES THAT WELCOME YOU TO A KOREAN MEAL. THEY GIVE YOU A GLIMPSE OF WHAT YOU’RE ABOUT TO EAT AND TELL YOU A LITTLE BIT ABOUT THE PERSON WHO MADE THE MEAL: WHAT THE PERSON CAN DO, HOW HE OR SHE THINKS, WHERE THE PERSON CAME FROM, HOW MUCH THE PERSON CARES. IT CAN BE AS SIMPLE AS KIMCHI AND SOME PICKLED CUCUMBERS, OR IT CAN BE AS ELABORATE AS A HUNDRED DIFFERENT INTRICATE LITTLE SIDE DISHES, LIKE YOU’D GET IF YOU WERE FEASTING WITH ROYALTY. AT HOME YOU’LL PROBABLY HAVE FIVE TO SIX PANCHAN. THESE WILL COME OUT FIRST, THEN STAY ON THE TABLE AS THE REST OF THE DISHES COME OUT. THE MEAL IS EATEN FAMILY STYLE, SO BY THE TIME EVERYTHING IS SET DOWN, THERE WILL BE DOZENS AND DOZENS OF SMALL PLATES AND BOWLS AND DISHES ON THE TABLE, WITH EVERYONE PICKING AT WHAT THEY WANT WITH THEIR CHOPSTICKS.

She sold her kimchi and panchan at house parties and bowling alleys and parking lots while pregnant with my sister. She was like the Avon lady, but instead of makeup, it was kimchi calling. Free savory pancake with any purchase. What a deal!

“Open a restaurant,” everyone would say to my mom after eating her food. And after their jewelry business went belly-up, my parents realized that, hey, they should open a restaurant. Move their underground hustle above ground. There was another kyae meeting. They combined their savings with the kyae pot and looked south to plant their seeds.

Our restaurant was in Anaheim, California, barely five miles north of Disneyland, on a long, never-ending boulevard called Brookhurst Street. Brookhurst runs almost twenty miles from Huntington Beach north through the Vietnamese ex-pat community Little Saigon in Westminster, up through the OC’s own Koreatown in Garden Grove, all the way into the barrios of Anaheim. We were in the western part of those barrios.

When we opened the restaurant there in 1978, West Anaheim was what you could call trashy, a transient hood. Some residential pockets did take root, but for the most part the homes weren’t where the heart was. The blood that ran through the veins of the neighborhood was a bit less wholesome: dive bars, drugs, Harleys roaring through the parking lot in front of the Humdinger, where girls danced nightly. As for Korean food, there were some noodle joints and a few small sul rong tang joints specializing in beef marrow soup, but that was it. Opening a big, family-friendly Korean restaurant in a place like that was like opening the only Korean restaurant in Hell’s Kitchen back when it was Hell’s Kitchen.

But that’s why the area was so cheap. And cheap real estate, as you know by now, is like a ghetto birdcall for Koreans. Our new home was just a few miles from its cultural cousins in Little Saigon and Garden Grove, but it may as well have been a hundred.

I WAS EIGHT when we started work on the restaurant. We called it Silver Garden, after my sister, just born. Her English name is Julie, but her given name is Eun-Jung, which means—well, you guessed it. All the family love was poured into our little girl. It’s an Asian thing, y’all. Prosperity and future, pride and no prejudice. Your children’s names are the waters that cleanse and sprout new life.

Before we took it over, the restaurant had been an Italian-American joint—emphasis on “American”—and we made it our own right quick. The restaurant’s sign was Winnie-the-Pooh yellow, with huge black letters and the Korean lettering—Eun Jung Shik-dang—just to the left of the English translation. “Silver Garden” was just one name crammed on a strip-mall signboard, just one business stuffed onto a strip of concrete with six other businesses, lined up like ducks in a row. We were the odd duck out, though, tucked between a used-appliance store and a silkscreen T-shirt shop. Just a few hops down

were a couple of choice dive bars—Sherwood Inn (“Cocktails, Hot Fantasies”) and Sugar’s (“Beer—Girls—Pool”)—plus a hobby shop, a takeaway BBQ rib place, a liquor store, and a nail salon.

The first thing you’d notice about Silver Garden was that almost the entire storefront was floor-to-ceiling plate glass. You know that glass that encapsulates car dealerships? The kind of glass that wobbles when fire trucks roll by? That kind of glass made up the front of Silver Garden. The front door was glass, too, with a long handle that braced its center like a belt. Rice paper framed by bamboo square boxes tic-tac-toed the bottom half of the front facade. Open the door, scrape. The door always stuck. Pull hard. Boom.

First thing to greet you: a cigarette machine. On the wall to your left, a corkboard pinned with calendars, business cards, flyers, couches for sale. Slope right. Walk into the main dining room. Enter the magic.

Rice paper with bamboo trim covered the walls, and my parents hung up antique tools from Korean farms—brooms, fruit-gathering baskets, hatchets, drying baskets for fish and chiles—for decoration. It was dark in here, but not so dark that it was depressing. A bamboo and rice paper room divider split the dining area into two; on the right side, big leather booths studded with brass buttons lined the wall, and brown Formica tables and stackable polyurethane chairs arranged into four-and two-tops took up the rest of the floor space. On the left side of the divider, larger tables in the same Formica. This side was the party room.

As you headed toward the server area, the place began to lighten up until bright white light swallowed the dark. This was exactly the line where the back of the house met the front of the house; in fact, you could literally stand right on this border, and half your body would be brown and the other half white. Ha!

When you stepped into the kitchen, you’d note how huge it was. There was a soda machine on the right, then the hand sink, water station, ice bin, and a stand-up refrigerator. To the left against the dining room wall, a piano of burners. The grill was on a side wall, and the center was filled with a prep table, stainless steel shelving, and a dishwashing area.

There weren’t too many cooks in the kitchen. There was my mom, the chef at Silver Garden, always elbows-deep in kimchi-stained plastic tubs. There was a dishwasher dude, a couple of older ladies helping with the kimchi and marinating meats, a cook putting out stews. Then my dad, doing whatever my mom told him to do. It don’t matter whether you are classically trained, a chef is a chef, and you do as the chef says. Yes, chef!

It was just this tiny group of people, but the kitchen was constantly busy, and the food never stopped coming.

Every morning before the restaurant opened at 11:00, the kitchen went into overdrive. The back alley was an orchestra of food: Porcelain barrels of fermenting bean paste lined up around the door like pipe organs. Right next to these barrels were salted fish, croakers or mackerels, hung and tied together, accordion style. In the pit of the alley were crates and crates of onions, scallions, garlic, mung beans, soybean sprouts, ginger. My auntie—a distant relative, actually, but the kind of relative you gotta call “auntie”—would strap on rain boots and wash all the vegetables down with a red hose. She was a short woman with a gold tooth and beautifully wrinkled skin. We have a joke in Korea: there are three types of humans—man, woman, and, for certain women of a certain older age, ajuma. She was definitely an ajuma.

The vegetables sun-dried on milk crates and old clothing racks. As they dried, we’d bring them into the kitchen for prep, and they’d inevitably land in one plastic bucket or another. There were buckets on the floor for the marinated spicy crab and sesame spinach. Other buckets for the short ribs marinating in thick black sauce. More buckets for the mountains of kimchi waiting for salted baby shrimp and oysters to be added. On the counter, flat chives laid out alongside big cubes of daikon and young baby radishes painted in red, all diced and cut, ready to be crunched in your mouth. Big blenders overflowed with savory pancake mixes.

Past all the buckets and blenders was the dry storage: cases of soju and beer, bags of dried chile flakes, sacks of unpeeled garlic and onions, jars of unpeeled ginger, kochujang, cucumbers, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, and pounds and pounds of rice. Then there were the cases of oranges and apples; once sliced, they were strictly reserved as our dessert for the guests.

Just off to the side of the kitchen in the very back of the restaurant was an amazing particleboard trapezoidal structure, a little island my parents built for my sister and me, which we turned into the Choi Family Treehouse. Two big couches, a couple of lamps, a 19-inch television on a swiveling pedestal, a twin bed with striped sheets, a baby playpen, a crib for my sister, a bookshelf, a desk. This was the scene of much of my third- to sixth-grade elementary-school education, where I did my homework, read books, solved multiplication tables, learned my prepositions and adverbs—did everything I needed to do to stay at the head of my class. I’d get out of school, pick up my little sister from day care, maybe take her by the supermarket, where I’d swipe a few candies for us, walk to the restaurant, and, while the kitchen was in full prep mode, settle us down in the Treehouse. She’d take her nap, I’d start on my homework, someone would be hosing the vegetables outside, someone else would be whack-whack-whacking at some piece of meat, everyone working at his own station until . . .

Three P.M. Regardless of what you were doing, everything came to an immediate halt at 3:00 P.M. At exactly three o’clock on the dot, it was dumpling time. Family time. The ladies took off their aprons, plunked down at booth number one, poured flour on the table, and set down a stack of dumpling wrappers and a big mound of ground meat laced with vermicelli noodles, ginger, scallions, garlic, soy sauce, sesame oil, and fish sauce. Time stood still as the women took the tips of their tablespoons, scooped up just the right amount of meat into the palm of their hands, dropped it into a dumpling wrapper, brushed on the egg wash, folded, and pressed. Then again a thousand times more.

And all the while, they talked shit.

“Yah, did you hear that Eun Ja got a new Mercedes? That ho been tricking for a long time, and now she finally got a sugar daddy and thinks she’s all that. It’s a nice car, though. . . . Yah, what are you gonna do about what Jee Su said about you? She said you left her with the bill and didn’t offer to pay because you guys have no money now and she says that you guys are gonna have to file for bankruptcy. She says that your kids are doing no good in school but her kids just got a summer scholarship to UCLA. . . .

“Yah, do I look fat? Yah, I want to get my eyelids done. Do you think I’ll look good? Looklooklook—what do you think? Should I get them done? Should I? . . . Yah, does your husband just come home and fart all day and throw his shit everywhere? . . . Yah, did you hear about the new beef soup place in Garden Grove? Wanna go? But I heard the sisters are fighting there now and the food went downhill. . . . Yah, let’s go shopping. That new stuff from Loehmann’s is on sale, and we can get some noodles afterwards. Hurry.”

Men, money, hair, wrinkles, gossip, new ventures, books they read, the old days. Anything. Everything.

Time went back on the clock around 4:00 P.M. That’s when the dinner rush hit. And that rush was almost always for our signature dish, the hot pot.

The hot pot. Twelve bucks for a family-style serving of spicy kimchi-tofu with shiitake mushrooms, vermicelli noodles, pork neck, shrimp, crab, rock cod, leeks, and a raw egg swirled in seconds before you eat it. The hot pot was served in a tin bowl shaped like a flying saucer with a hole in the middle. Heated by a can of Sterno underneath the saucer, the stew swirled and boiled around in the doughnut ring of heat.

To accompany the hot pot, you could get a warm tofu or rock cod dish braised in soy sauce and rice vinegar, topped with shaved scallions and toasted sesame seeds. And some salted croaker fish and the raw spicy crab, too. And of course you couldn’t leave without a plate of panfried dumplings and grilled short ribs. Then, as the Sterno began to sputter, you could mash the rice into the bottom of the stew and turn it in

to deliciously crispy bits. On top of those greatest hits we had our B-sides. There were twenty-five to thirty dishes on the menu in total, divided into sections for BBQ, stews, soups, dumplings, hot pots, noodles, and rice, plus specials like braised kalbi. All between five and twelve bucks.

At its busiest, the restaurant did two hundred to three hundred covers a night. That’s fuller than full—lines-out-the-door full. And that’s because nobody, I mean nobody, was doing food as good as Silver Garden back in that day. If Yelp were around back then, Silver Garden would have been on the home page with 4.5 stars, there would have been lines out the door, and there would have been food blogs decorated with photos of that hot pot.

But this was the late seventies and early eighties. We had to rely on the original form of Yelping: old-fashioned word of mouth. And, damn, word got out fast. Our crowd included the occasional white and Indian folks, but the restaurant was mostly crowded with the small but fierce community of Koreans in Anaheim. We had friends who rolled in a few times a week. Then there were Korean groups who came in after work. Korean guys hungry after a few rounds of golf. My dad took care of these crowds, and the two waitresses—usually young Korean exchange students or little sisters of my mom’s friends—took care of the orders.

And me, why, I played maître d’. Before everyone came in, I took care to Windex the front door and windows, made ’em real shiny and clean. I checked on all the tables, made sure the settings were right, had a Coke while waiting for the crowd to arrive. And when they did, I posted up by the cigarette machine and said “Welcome to Silver Garden” and told them they could sit anywhere. Then I’d give a wink to the cute waitress cuz I was a cool cat with a cool little crush on a cool little coed. She’d wink back and greet the table. Every once in a while I’d go back to the Treehouse to check on my sister and take a break to watch TV or read a book with her. Then I was back out on the floor, part of the laughter and the roar, refilling the panchan and water glasses.

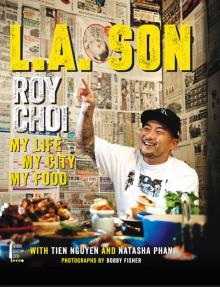

L.A. Son

L.A. Son